Cross-posted at Skeptical Science

The 97% consensus on anthropogenic global warming (AGW) reported by Cook et al. (2013) (C13) is a robust estimate. Alternative methods, such as James Powell’s, that identify only explicit rejections of AGW and assume that all other instances are endorsements, miss many implicit rejections and overestimate the consensus.

The C13 method can be modified and used to estimate the consensus on plate tectonics in a sample of the recent geological literature. This limited study—not surprisingly to anyone familiar with the field—produces a consensus estimate of 100%. However, among the abstracts that expressed an opinion. only implicit endorsements of the theory were found: this underlines the importance in consensus studies of identifying implicit statements. The majority of the abstracts expressed no position. Assuming that these cases suggest either uncertainty about, or rejection of, plate tectonics (as some critics of C13 have claimed about AGW) would lead to the absurd conclusion that the theory is not widely accepted among geologists.

Opinion surveys show that the public is misinformed about true state of consensus among climate scientists, with only a minority aware that it is greater than 90%. The difference between 97% and 99.99% is tiny compared to this gap. The 3% of published papers that reject AGW are contradictory and have invariably been debunked. They do not therefore provide a coherent alternative account of climate science. Despite this, dissenters are awarded disproportionate attention by ideologically and commercially motivated interests, as well as by false balance in the media. Countering this public confusion requires both communicating the consensus and debunking bad science.

For a shorter summary than the one below, read Dana Nuccitelli’s Guardian piece: Is the climate consensus 97%, 99.9%, or is plate tectonics a hoax?

In 2016, James Powell published an article Climate Scientists Virtually Unanimous Anthropogenic Global Warming Is True in the Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society. The paper was critical of the 2013 paper by John Cook and members of the Skeptical Science team (C13): Quantifying the consensus on anthropogenic global warming in the scientific literature. Powell’s article is pay-walled, but readers can read the details of his argument on his blog and in a Skeptical Inquirer piece from 2015. There is also a free version of the BST&S article hosted here, found through the Unpaywall Browser Extension.

We have previously responded to Powell’s arguments. John Cook published an article for Skeptical Inquirer and I wrote a piece on my blog Critical Angle. Yesterday, a team of eight co-authors (Andy Skuce, John Cook, Mark Richardson, Bärbel Winkler, Ken Rice, Sarah Green, Peter Jacobs and Dana Nuccitelli) published a more formal, peer-reviewed rebuttal: Does it matter if the consensus on anthropogenic global warming is 97% or 99.99%? in the Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society. The article is paywalled, but the publisher allows us to post a version of the revised submitted manuscript, which can be read here.

In his BST&S paper, Powell makes four main arguments against C13:

- Consensus studies by Doran & Zimmerman (2009), the Pew Research Center (2015) and Anderegg et al. (2010) fail to reveal a near-unanimous consensus on AGW “…because of some combination of small sample size, reliance on fallible opinion, and inclusion of nonexperts…”

- The C13 study of 11,944 articles in the peer-reviewed literature from 1991-2011 failed to adequately measure the consensus because it ignored the abstracts and papers that did not express an opinion on AGW.

- Applying the C13 methodology to a universally accepted theory like plate tectonics would yield misleading or absurd results.

- If it were true that 3% of scientists rejected or were uncertain about AGW, then the case for action to prevent global warming would be weakened, since, by comparison with now-settled scientific questions like continental drift and the origin of lunar craters, the existence of dissenters might suggest that AGW theory was about to be overthrown

We respond in detail to these objections in the paper. I will summarize the main points below. Complete references are provided in the paper.

James Powell has written a rejoinder to our article, which should be published in coming weeks. We have not seen it yet.

1. Did previous studies fail to reveal a near-unanimous consensus?

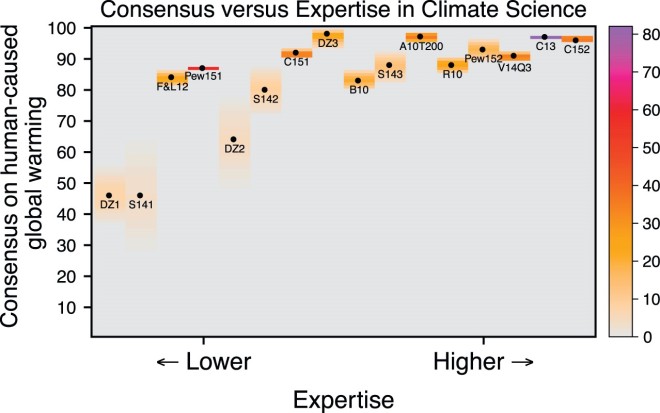

This point is best addressed by referring to the meta-study Consensus on consensus: a synthesis of consensus estimates on human-caused global warming published in 2016 by John Cook and 15 co-authors. (C16). The study found that different studies using different methods produced estimates of the consensus on anthropogenic global warming (AGW) that range from 90-100% for sampled populations with expertise in climate science. Within this range, the results differ because of: “variations in the study timing, definition of consensus, or differences in methodology including surveys of scientists, analyses of literature or of citation networks.”

Although the studies show that multiple lines of evidence exist for overwhelming support among climate experts for AGW, most studies do reveal a small percentage of dissenting opinions. The degree of consensus correlates with increasing expertise.

From C16. Level of consensus on AGW versus expertise across different studies. Right colour bar indicates posterior density of Bayesian 99% credible intervals. Only consensus estimates obtained over the last 10 years are included (see S2 for further details and tabulation of acronyms).

2. Did C13 underestimate consensus?

Powell has two main objections to the C13 methodology.

Firstly, he argues that all abstracts that do not contain an explicit rejection of AGW should be deemed to endorse AGW. There is circularity to this argument: the assumption of near-universal endorsement leads Powell to classify any abstract lacking explicit rejection wording as endorsement. We found that implicit rejections of AGW were much more common than explicit rejections. Indeed, in our supplementary survey of the original authors, 1.8% of those who responded classified their own papers as rejecting the consensus on AGW.

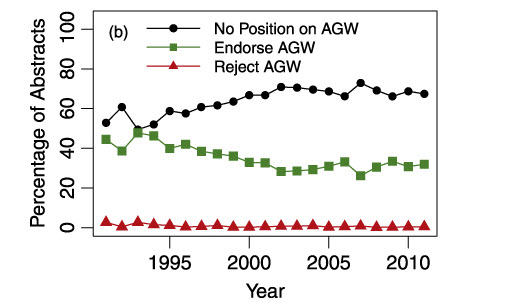

Secondly Powell claims that C13 ignored the “no position” abstracts. In fact, we did plot the percentage of “no position” abstracts over time and noted that these showed an increasing trend. Although it is somewhat counter-intuitive, we would expect no-position abstracts to increase as the acceptance of AGW rises with time. Space is limited in abstracts and scientists may consider that an endorsement of AGW would be stating the obvious. As we will see in the next section, in geological journals in 2015, abstracts that do not take a position on plate tectonics range from 55-76%. This is not because geologists are hesitant about the reality of plate tectonics, but rather that making implicit or explicit endorsements is either superfluous or irrelevant to the specific research topic of the paper.

From C13, Figure 1 (b). Percentage of endorsement, rejection and no position/undecided abstracts. Uncertain comprise 0.5% of no position abstracts.

It is true that the “no position” abstracts were not used by C13 in the estimate of consensus. Because the authors provided no text that revealed their opinion, we didn’t try to guess it. Nevertheless, we accept that the authors of the great majority of “no position” abstracts most likely accept AGW—but not all of them.

3. Can the C13 method estimate the consensus on plate tectonics?

We performed a small study applying the C13 methodology to consensus on plate tectonics. We looked at the abstracts of papers published in 2015 in the journals Geology and the Journal of the Geological Society. These journals were chosen because they are widely cited and publish articles over the full gamut of solid-Earth geoscience.

We chose criteria for the implicit endorsement of plate tectonics to be uncritical mentions of key elements of the theory, such as sea-floor spreading, subduction or continental drift. References to global-scale paleogeographic features such as Pangaea or Tethys Ocean would also qualify as implicit endorsements.

We looked for explicit endorsements of plate tectonics, but found none. This is not surprising. It is very unlikely that any scientists would put a statement like “plate tectonics is true” into a research abstract in 2015. Nor did we find any rejections of any kind. This also is unsurprising: although there are extremely rare dissenting articles written, even in recent years, it is very unlikely that they would pass peer-review in a prominent journal.

Our rating results:

Of the 265 Geology abstracts, 65 (24.5%) were rated as “implicit endorsements” and 200 (75.5%) were judged to be “no position”. The Journal of the Geological Society yielded 30 (45.5%) “implicit endorsement” and 36 (54.5%) “no position” ratings. Using the C13 methodology for calculating consensus (i.e., the number of endorsements divided by the sum of endorsements and rejections) yields 100%.

The purpose here was not to establish a definitive consensus study of plate tectonics, but to explore whether a modified form of the C13 method could be applied outside the field of climate science. A much broader sample of journals would be required for a comprehensive consensus study and there is a possibility that more obscure journals might publish a very rare paper skeptical of plate tectonics. A study of the growth of the consensus over time, particularly in the decades following the 1950s would be interesting, but would require a major effort.

Our main findings:

- Yes, the C13 methodology works for plate tectonics, because it counts implicit endorsements. Relying solely on explicit endorsements or rejections would not work because such statements, in abstracts in recent papers in prominent journals at least, are essentially non-existent.

- Most of the abstracts do not take a position on plate tectonics. This is the case even though plate tectonics provides the fundamental framework for modern geology. The reasons for this are partly because some of the articles didn’t require any consideration of plate tectonics processes in their specific research focus (e.g. in geomorphology, glaciology, mineralogy). Failure to endorse the theory should not be taken to imply any uncertainty among geologists. The differences in the percentages of “no position” abstract between the two sampled journals possibly reflects a difference in editorial preferences of subject matter, but this would need to be demonstrated by further study.

- Some critics of C13, for example Legates et al (2013), claim that only explicit, quantified endorsements of global warming being caused mostly by humans should count towards a consensus on AGW. Using this approach, they calculated a consensus on AGW of 0.3%. If they applied the same criteria to plate tectonics they would get a consensus of zero, which is equally absurd.

- We don’t expect (but never say never!) that our small study will attract the kinds of hostile commentary that the C13 study has received. Those criticisms included, for example: that the raters were biased (we certainly are not neutral on plate tectonics); or that the results are suspect because raters colluded privately (we did freely compare and discuss ratings in the plate tectonic case, but only in a handful of problematic instances for the C13 study); or failed to keep to-the-minute time stamps (we didn’t here, either). The reason we don’t expect controversy is because AGW is politicized and doubt about it is largely manufactured and exaggerated by ideological and commercial interests. Plate tectonics has never attracted this kind of controversy, motivated by concerns outside of science.

- Everyone can see the reasons for our ratings in this document. The abstracts are freely available online and our ratings can be checked and replicated.

4. Does a 97% consensus imply a significant level of doubt?

Does the existence of a small percentage of scientists who doubt AGW pose a threat to the mainstream view or indicate the beginning of a scientific revolution? It might, if the dissenters could agree on a single consistent alternative model that accounted for the majority of observations. The reality is that the contrarian objections are incoherent and they contradict each other. They have also been widely debunked. Science revolutions occur when comprehensive alternative theories with greater explanatory power emerge. There is no sign of this happening in climate science.

Attempts to draw parallels between scientific revolutions in the past and the current situation in climate science, as Senator Ted Cruz and others have proposed, are based on false history. It is rare that a well-established general scientific theory is overturned by a handful of plucky skeptics.

For example, sustained resistance to the heliocentric ideas developed by Copernicus, Kepler, Galileo and Newton came not from scientific rivals, but from religion. It is ridiculous, pretentious even, for climate science contrarians to compare themselves to Galileo.

Modern climate science itself emerged gradually from the mid-nineteenth century. Although there were disputes and problems along the way—typical for a developing science—improved models and new observations allowed the current consensus to form. Organised opposition to the consensus emerged once it became clear that the science implied that policy measures were required to reduce emissions to limit warming.

The controversy over continental drift that raged in the early twentieth century was only partly about the evidence. The reality was that the key data about the nature and age of the crust underlying the oceans was almost completely lacking then, so both sides were speculating about the age and nature of a crucial two-thirds of the Earth’s crust.

A major factor fueling the debate was methodological. North American geologists favoured an inductive, multiple-working-hypothesis epistemological model, whereas Europeans were more comfortable with theory-first reasoning. This is all explained in Naomi Oreskes’ excellent book The rejection of continental drift: Theory and method in American earth science.

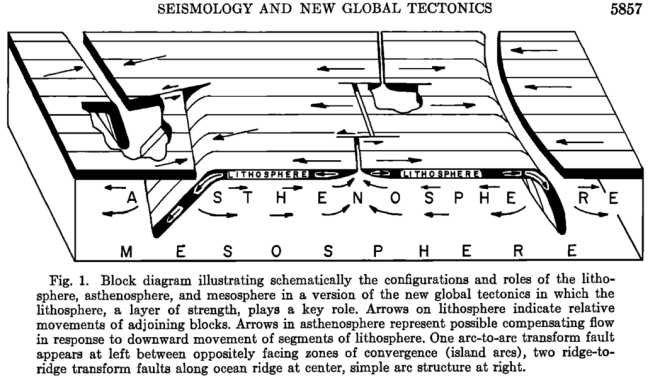

As new data came in and a unifying kinematic model emerged—plate tectonics—methodological objections disappeared and almost all geologists embraced the new theory within a decade. See also my blog post Consensus on plate tectonics and climatescience for further discussion.

From Isacks, Oliver and Sykes, 1968. Like the Dude Lebowski’s rug, this diagram and this one really tied the geological room together.

Hardly anyone but a few cranks oppose heliocentrism or plate tectonics these days. Current objections to AGW were amplified after nearly all climate scientists became convinced by multiple lines of evidence that human emissions were driving global warming. These objections were not usually put forward by scientists convinced that they were in possession of a better model, but by people whose ideology or commercial interests were threatened by the implication that prudent policy requires rapid reduction in the use of fossil fuels.

Discussion

Why is communicating the consensus on AGW important? Mainly, it is because the public, the American public especially, has been deliberately misinformed about the level of scientific dissent. Most people do not have the time or the ability to assess the scientific evidence for themselves. They rely on heuristics, such as what the experts have concluded. People do this every time they accept a physician’s treatment recommendation and every time they drive across a bridge designed by professional engineers. None of us are polymaths in the modern world, able to go to primary sources and evaluate them as if we were specialists. We are obliged to rely on the opinions of credible experts. There was a day when smart people could live by a principle such as “taking nobody’s word for it”. But today is no longer that day. Modern science has become too vast and specialized for any individual to master it all. Most experiments and observations are now beyond the reach of amateurs.

In a world in which the objections to the mainstream conclusions on AGW have been deliberately inflated, communication of the overwhelming scientific consensus becomes vital to keep the public’s discourse on policy rooted in reality. Studies have shown that such communication leads to changes of test subjects’ opinions and reduces the biasing influence of ideologically motivated actors. Furthermore, it has been shown that consensus estimates act as a “gateway belief”. Manufactured low consensus estimates close the gate, inhibiting further consideration. On the other hand, acceptance of the true, high estimates of scientific consensus unlocks the gate, permitting further investigation of the science and, crucially, encourages necessary reality-based discussion of policy options.

Conclusions

There is a very small but real percentage of scientific opinion that rejects mainstream conclusions on anthropogenic global warming. Such opinion is incoherent, usually ideologically motivated and invariably debunked. Literature surveys that rely solely on finding explicit rejections of AGW will miss the more numerous implicit rejections that are implicitly expressed or are present in abstracts that express no clear opinion. James Powell’s approach, which counts only explicit rejections and assumes that the rest of the literature endorses AGW, exaggerates the consensus a little.

It ought not to matter whether the consensus is 97% or 99.99%. Either figure demonstrates a near-unanimous endorsement. Unfortunately, today’s political and media environment gives a disproportionate degree of attention to the small minority of dissenters. The public has become understandably confused and opinion surveys consistently reveal that the perception of the degree of scientific rejection of climate change is larger than it is.

This misconception needs to be tackled head-on, by repetitively asserting the overwhelming scientific support for AGW. In addition, mainstream scientists need to examine and publicly debunk scientific notions that reject the consensus view.

Many years ago, a geology professor gave me some sage advice: “Never exaggerate your case, it only makes it easier to argue against”. We don’t need to claim that 99.99% of scientists conclude that global warming is real and largely man made. It’s quite sufficient to demonstrate that dissenters make up only a very small percentage of scientists, that their theories provide no coherent alternative and that their scientific arguments are debunked.

Postscript: You can say that again

My colleagues and I talk a lot about consensus. Many of us would instead prefer to focus on the amazing new science being produced and on the daunting policy challenges that humanity faces in avoiding harmful climate change. Sometimes I worry that the repetitive messaging is becoming a bit boring.

In the recent congressional hearings on science organised by Republican politicians, only one mainstream scientist, Michael Mann, was invited as a witness for the 97%. Everybody at the meeting kept bringing up consensus, either to affirm it or deny it.

Here’s a brief video supercut made by John Cook of the mentions of consensus at the meeting that he made for the excellent Evidence Squared podcast series that he presents with Peter Jacobs:

Evidently, consensus still matters to scientists and politicians alike and on both sides of the so-called debate. But even as we repeat the consensus message, we are faced with the reality of an American government that rejects climate science and is hell-bent on removing regulations to mitigate emissions. It’s all rather disheartening—but there are glimmers of movement.

Even though most conservatives have expressed consistent opposition to climate science and mitigation regulations—perhaps motivated by the need to show adherence to their cultural groups, as Professor Dan Kahan and others have argued—recent surveys have shown that there are surprising levels of support for climate and pollution mitigation policies, even among President Trump supporters.

“The main finding for the survey is that Trump voters are more supportive of climate action — and much more supportive of clean energy — than most people might have assumed,” said Edward Maibach, a professor at George Mason University and a co-author of the study. “I suspect even Mr. Trump would be surprised by this finding.”

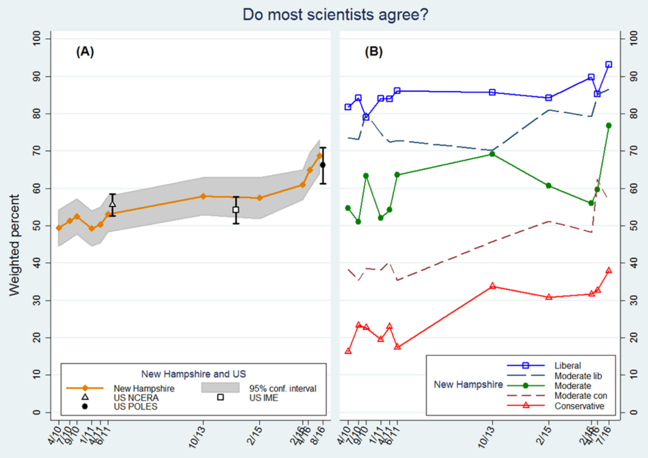

In a recent paper, Larry Hamilton of the University of New Hampshire reports that there are initial signs of growing awareness of the scientific consensus, in his surveys of the public in New Hampshire. He notices an uptick in recent years, with liberal perceptions of consensus rising from the mid-80% to the mid-90% and among conservatives from 30% to 40%.

Percentage who think most scientists agree that human activities are changing the climate. From Hamilton, 2016, figure 3.

Percentage who think most scientists agree that human activities are changing the climate. From Hamilton, 2016, figure 3.

Of course, it is not possible, using these data alone, to attribute this recent rise to any single factor. Nevertheless, Hamilton writes:

Growing awareness of the scientific consensus, whether from deliberate messaging or the cumulative impact of many studies and publicly engaged scientists, provides the most plausible explanation for this rise in both series [viz., public opinions on human-caused climate change and on perceptions of the degree of agreement among scientists].

Perhaps we can draw some encouragement from this. But there’s still a very long way to go. And we have to make haste: nature is not about to slow down its physical processes to provide more time for humans to get over their cognitive dissonance and wishful thinking.

Acknowledgement. We thank James Powell for his discussion of the C13 paper. His critique prompted us to provide elaboration of our methods.

Pingback: New publication: Does it matter if the consensus on anthropogenic global warming is 97% or 99.99%? – Enjeux énergies et environnement

Pingback: 97% vs 99.99% | …and Then There's Physics

Talk about your zombie arguments… Those who have previously published papers saying the consensus is 97% still think so. Hosanna and hark the revolution.

However, when actual climate scientsts survey other actual climate scientists, the results are very different. Bray von Storch et al, find a very robust, but much lower 66%. Verheggen et al replicate the result.

You don’t need a 97% or 99% consensus to move science forward. You only need it when you have to justify RICO investigations and witch hunts.

We mention the Bray and Verheggen results in Cook et al 2016 (Verheggen is a co-author). The point “B10” in the first figure above is taken from Bray (2010).

It is not the intent of these studies to move the physical science along. The physical scientists already know that only a few cranks dispute the basic science of AGW. The main reason for studying it is to correct the deliberately promoted and meretricious notion that there is widespread dissent among scientists.

I don’t want to see RICO investigations or witch hunts. Those would be distracting and unproductive. I simply hope for stronger action on reducing emissions.

As do I. But this type of exercise is distracting, not helpful.

Indeed our Groundskeeper seems easily distracted by consensus studies, since he comments them all. So much concerns to distribute, so little time.

This sentence misses a few words, AndyS:

> Indeed, in our supplementary survey of the original authors, 1.8% of those who responded to classified their own papers as rejecting the consensus on AGW.

Thanks, I took out a stray “to”. I hope it makes sense, now.

If the 97% consensus Cook 2013 found is supposedly defined as something like “most (greater than 50%) of the recent warming is anthropogenic” then the categories “explicit endorsement without quantification” and “implicit endorsement” make no sense. Simply because an abstract can’t endorse such a consensus without containing some quantification of the amount of warming that’s anthropogenic. Similarly, it also can’t “implicitly” support something which requires quantification for endorsement.

So the 97% consensus cannot be as defined above.

If you just compare the categories 1 and 7 (the abstracts that actually contain quantification) then you get 87% from the 65 papers in those categories or 96% from the 200/300 or so self-rated papers in those categories. In either case that is a very small, and not representative sample (it’s basically going to be attribution studies).

If an abstract talked about global warming and only mentioned one cause, human emissions, we took that as an implicit endorsement. As an analogy, if an abstract talked about lung cancer and mentioned only smoking,among all possible causes, we could reasonably take this as an implicit endorsement that smoking is the main cause.

Similarly, if an abstract mentioned global warming but only mentioned, let’s say, solar cycles, we would have rated that an implicit rejection, even if they neglected to say exactly how much solar cycles contribute to observed global warming.

Of course there is some subjectivity involved in identifying such ratings. One way we tested the robustness of our result was to email the authors to invite them to rate their own papers. This produced essentially the same result. Another way was to provide a ratings tool on the Skeptical Science website to invite anyone to do their own ratings. So far, nobody has taken us up on this.

For someone to rebut our result and demonstrate a lower consensus, all they would have to do is identify more than 3% of the abstracts in our sample as rejecting AGW. Again, nobody has been able to do this. The reason, is, I think, because those abstracts do not exist.

It is true that the number of abstracts that make explicit, quantified statements of attribution in their abstracts is small. What we were trying to establish was the general level of consensus in the climate science beyond the specialty of attribution studies. More particularly, we were attempting to falsify the notion that dissent on the causes of global warming is widespread. It’s not.

I might add that if you applied an explicit-only criterion to determining the degree of consensus on plate tectonics in the recent geological literature, you would find very few such statements in abstracts, or even none at all, as we did in our small study reported in our recent paper. Implicit endorsements are much more numerous, although the majority of geological abstracts are silent on plate tectonics, even though the concept is now universally accepted as the unifying theoretical framework of modern geology.

I would guess that you would find the same thing in investigations of the biological literature about the consensus on evolution by natural selection. However, you would probably find more dissenters on evolution than you would on plate tectonics, because the religious/ideological motivation to deny evolution is strong in some parts of society. Moving plates don’t seem to cause any ideological earthquakes among any religious or political groups.

The example for the implicit endorsement category given in the paper is:

“…carbon sequestration in soil is important for mitigating global climate change”.

“Important for mitigating global climate change” doesn’t equal “human emissions are the main cause”.

The example for the explicit endorsement without quantification category is:

“Emissions of a broad range of greenhouse gases of varying lifetimes contribute to global climate change”

“Contribute to” doesn’t equal “main cause”.

Regarding identifying more than 3% of the abstracts in the sample as rejecting AGW, to which sample are you referring? If it is the sample comprising the papers in categories 1 and 7, then there are 13% rejecting (or rather minimising) AGW from the ones you studied, or 4% from the self ratings. Source:

https://skepticalscience.com/debunking-climate-consensus-denial.html

“The IPCC position (humans causing most global warming) was represented in our categories 1 and 7, which include papers that explicitly endorse or reject/minimize human-caused global warming, and also quantify the human contribution. Among the relatively few abstracts (75 in total) falling in these two categories, 65 (87%) endorsed the consensus view. Among the larger sample size of author self-rated papers in categories 1 and 7 (237 in total), 228 (96%) endorsed the consensus view that humans are causing most of the current global warming.”

Sorry, I said 65 in total for 1 and 7 earlier. Should have said 75 in total.

No, I meant >3% among the 11,000+ abstracts we had in our sample. Any other representative sample of the literature would do.

It is true that the example we quoted does not explicitly state that GHGs are the main contributors. It’s possible, of course, that the main body of the article text (which we didn’t examine in the abstracts-only part of our work) contained arguments that GHGs are a minor component of GW and the authors forgot to mention the main alternative contributing factors in their abstract. [Note, original comment corrected] It could be reasonably argued that this should have been rated as an implicit endorsement, I’ll grant you that, and I wish we had chosen a clearer example.

Out of the 11,000+ abstracts in the sample, only 75 papers (or 237 self ratings) actually express whether they endorse or reject the IPCC position of humans causing most of the warming. That’s according to the quote from your co-author Dana Nuccitelli. You say that it’s possible the main body of the article text contained arguments that GHGs are a minor component of GW, but I would argue that’s not necessary. If the rest of the paper mentioned nothing about any other components to GW, whilst the abstract mentioned human emissions as a cause (or contributing factor), then the paper still doesn’t endorse the idea that human emissions are the main cause of GW. It would be either “no position”, OR you could say that since it mentions human emissions as a cause (or contributing factor) that it endorses a consensus with a definition along the lines of “human emissions contribute to warming” or perhaps “AGW is true”. You can’t say it endorses a consensus with the definition “humans are causing most (greater than 50%) of warming” because it doesn’t actually say that in the abstract or anywhere in the paper. If it did, it would be in category 1. It would be one of the 65 (if just in the abstract) or one of the 228 (if self-rated) in that category.

I corrected my previous reply before I saw this comment. I tend to agree with you that this short extract of an abstract, used an example of an explicit endorsement without quantification is not a good one. The full abstract is here, from this paper http://www.pnas.org/content/107/43/18354.abstract :

Because of the lack of any explicit mention in the abstract that GHGs are the main cause of warming it is reasonable to question the rating of this example. However, there’s no doubt that it would certainly deserve to be classified as an implicit endorsement and that, since our calculation of the consensus as 97% depends on the consolidated count of all endorsements, that headline result is unaffected.

It doesn’t actually matter for the significance of C13’s results how some critics of the paper interpret the ranking criteria. The crucial aspect is how the raters themselves understood and applied the criteria.

For the abstract rating, the raters’ own interpretation of the criteria has been explained many times over the past four years.

In the self-rating process, scientists were invited to rate their own papers using the same criteria. Depending on whether or not we include the “no-position” papers in the denominator, 1.8%-2.8% of these papers were rated by their own authors as implicitly or explicitly rejecting or minimizing the human role in causing global warming.

There’s no evidence that self-identified contrarians (or the other scientists who responded to the survey) misunderstood the criteria as presnted. Indeed, the fact that the proportion of rejectors to endorsers was close in both the abstracts and the self-rating process, helps support the case that the rating criteria were clear enough.

Subsequent to publication the main objections to C13 that came from contrarian scientists consisted of complaints that that the C13 raters had misclassified their papers as endorsements or “no-position”. None of these contrarian authors, as far as I know, commented that they ought to be included among the mainstream because they acknowledge a small human contribution to global warming.

To be sure, there may well be some misclassified abstracts in the C13 study. This is why we set up an online tool to allow everyone to rate the abstracts for themselves. None of our critics, except one, has attempted to do their own analysis. As I argued previously, to demonstrate that there are many more than 3% of the papers in the scientific literature that reject or minimize the role of humans in causing recent global warming, would not be difficult.

The only one of our critics who did his own survey of the literature was James Powell. He concluded that 97% was an underestimate, not an exaggeration of the true consensus on AGW. His substantive critique allowed us to engage in a useful discussion on methods.

It could be classified as an implicit endorsement. Essentially there is no meaningful difference between the implicit endorsement and the explicit endorsement without quantification categories. However, it implicitly endorses a consensus with the definition “humans emissions contribute to warming” rather than a consensus with the definition “human emissions cause more than 50% of warming”, because nowhere is it said or implied that human emissions cause more than 50% of warming. If it did, it would belong in the explicit endorsement with quantification category. Or possibly, a different category altogether (one that isn’t part of the study) – implicit endorsement with quantification.

> Essentially there is no meaningful difference between the implicit endorsement and the explicit endorsement without quantification categories.

Of course there is.

One is implicit and the other is explicit.

To see the effect in action, try to sell the numbers to contrarians without making that distinction.

Best of luck.

Your argument has been discussed to death at Bart’s years ago for months:

Check your first comment, AndyS.

Basically the explicit endorsement without quantification and explicit rejection without quantification categories can only be endorsing or rejecting a consensus with the definition “human emissions contribute to warming” rather than “human emissions are causing most (greater than 50%) of warming”, because the category is specifically “without quantification”. Therefore if your consensus depends on the “consolidated count of all endorsements” (which will include categories 1 and 7 that DO involve quantification), you are conflating two different definitions of consensus into one.

To elaborate, referring to part of a comment from Dana Nuccitelli at the link Willard supplied:

“Categories 2, 3, 5, and 6 do not quantify the human or natural contributions to global warming. That’s why they’re not Category 1 or 7.”

This confirms that the implicit endorsement and rejection categories (of course) also involve no quantification. Therefore papers in these categories may or may not endorse a consensus along the lines of “human emissions cause more than 50% of warming”; that simply can’t be said either way. So they can only really endorse or reject a consensus along the lines of “human emissions contribute to warming”.

So the results from 2 and 3 compared to 5 and 6 give you an estimate of the consensus with a definition such as “human emissions contribute to warming”; a consensus most climate change skeptics would consider themselves a part of.

The results from 1 compared to 7 gives you an estimate of the consensus with a definition such as “human emissions cause more than 50% of warming”; though with the limitations already mentioned in my previous comment.

Comparing the results from 1, 2 and 3 with 5, 6 and 7 to get that overall 97% figure would be conflating two different definitions of the consensus and thus a meaningless result.

> This confirms that the implicit endorsement and rejection categories (of course) also involve no quantification.

Interestingly, BrandonS pulled the exact same trick at Bart’s.

The AGW position hasn’t been formulated with an explicit quantification in C13. In fact, the explicit attribution statement made by the IPCC varied over the years. Making the quantification explicit would break its context sensitivity.

That contrarians insist in overinterpret “most” won’t change the fact that papers making explicit quantification were attribution studies. C13 evaluated an endorsement that goes beyond that specific realm.

I don’t mind much rehearsing this ClimateBall episode. At best this overinterpretation will lead to Lowell’s conclusion.

And as far as Powell’s result is concerned, we already know from Cook 2013 that there is likely to be only a very small percentage of papers in the literature which explicitly endorse or reject with quantification a consensus defined as “human emissions cause more than 50% of warming”. All he’s done is effectively looked through a bunch of papers, found the (expectedly) few category 7 papers, and then claimed, “well, the rest must be category 1”, when we know from the Cook paper that this assumption isn’t valid.

It isn’t a choice between 97% or 99.99%, both are wrong. In neither case does the result apply to a consensus defined as “human emissions cause most of the warming”. You can’t determine what the level of such consensus is from a literature survey for the simple reason that the vast majority of said literature doesn’t specify, either in the abstract or the full paper, how much of warming is due to human emissions.

If you want to know what the consensus is, survey climate scientists opinions. This has been done, as Thomas Fuller pointed out to begin with, and generally it is found to be lower than 97% or 99.99%.

This is certainly one way to try and estimate the consensus. Another is to analyse the literature.

The author of that study does not appear to agree with Tom Fuller’s interpretation. If you consider the sub-sample of publishing climatologists, the study that Tom Fuller is referring to suggests a consensus of around 90% (Table 1, Verheggen).

Powell’s reliance on identifying only explicit rejections of AGW was indeed part of the reason why his consensus estimate was high another reason was his assumption that implicit rejections and all of the n-position abstracts constitute tacit support for AGW. We disagree with that as we explain in our recent paper. It’s a bit like claiming ” those who are not unequivocally against us are for us” an inverted and paraphrased version of George Bush’s notorious comment after 9/11.

And yet Verheggen’s headline findings of climate scientists was 66%. Bray, von Storch found the same among published climate scientists. A larger proportion of published climate scientists in each study strongly agree with IPCC findings–these are not doubters. But especially in Bray von Storch we see very real concerns about data quality, as well as a pronounced distaste for exaggerating findings to spur concern in politicians and the public.

The methodology used in literature searches ranging from Oreskes’ Beyond the Ivory Tower to recent efforts by Cook and several of the commenters here ranges from not rigorous to not published. It’s great for politics. It’s sad for science.

I will be suspending comments here for a week of more. For personal reasons, I will not be able to moderate or comment for a while.

In the meantime, please feel free to comment on the same post at Skeptical Science. https://skepticalscience.com/S17blogpost.html