Cross-posted at Skeptical Science

The 97% consensus on anthropogenic global warming (AGW) reported by Cook et al. (2013) (C13) is a robust estimate. Alternative methods, such as James Powell’s, that identify only explicit rejections of AGW and assume that all other instances are endorsements, miss many implicit rejections and overestimate the consensus.

The C13 method can be modified and used to estimate the consensus on plate tectonics in a sample of the recent geological literature. This limited study—not surprisingly to anyone familiar with the field—produces a consensus estimate of 100%. However, among the abstracts that expressed an opinion. only implicit endorsements of the theory were found: this underlines the importance in consensus studies of identifying implicit statements. The majority of the abstracts expressed no position. Assuming that these cases suggest either uncertainty about, or rejection of, plate tectonics (as some critics of C13 have claimed about AGW) would lead to the absurd conclusion that the theory is not widely accepted among geologists.

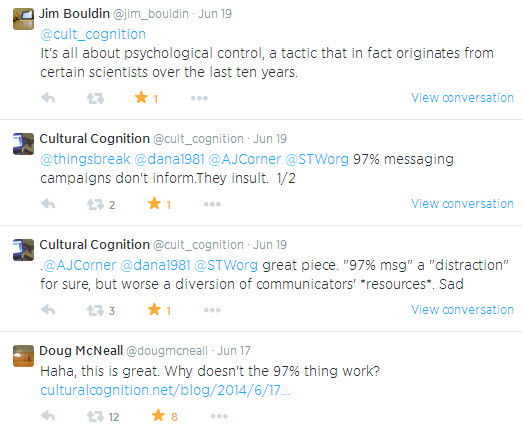

Opinion surveys show that the public is misinformed about true state of consensus among climate scientists, with only a minority aware that it is greater than 90%. The difference between 97% and 99.99% is tiny compared to this gap. The 3% of published papers that reject AGW are contradictory and have invariably been debunked. They do not therefore provide a coherent alternative account of climate science. Despite this, dissenters are awarded disproportionate attention by ideologically and commercially motivated interests, as well as by false balance in the media. Countering this public confusion requires both communicating the consensus and debunking bad science.

For a shorter summary than the one below, read Dana Nuccitelli’s Guardian piece: Is the climate consensus 97%, 99.9%, or is plate tectonics a hoax? Continue reading