The blog Skeptical Science is mainly concerned with “Explaining climate change science & rebutting global warming misinformation” and is mostly devoted to debunking the often nonsensical and incoherent notions that dispute the physical science of climate change. Occasionally though, the contributors to the blog—including me—write about solutions and policy. When we write about energy matters, we tend to focus on climate effects, but not so much on things like aquifer pollution from unconventional oil and gas operations.

In a blog post he titled Global warming believers for natural gas, Nick Grealy claimed that a post on Skeptical Science discussing the famous 2004 “wedges ” paper by Pacala and Socolow somehow endorsed the greatly expanded use of unconventional natural gas. just because it mentioned that one of Pacala and Socolow’s 15 wedges was about gas substituting for coal. Dana Nuccitelli quickly put him right in the comments.

Recently, Skeptical Science has run a series of posts about the recent research on fugitive methane releases from oil and gas operations. These include:

Methane emissions from oil and gas development

More research confirming methane leakage from shale boom

I also have written on British Columbia’s suspiciously low self-reported fugitive emissions. I published that work on this blog rather than on Skeptical Science, because this particular issue has a local rather than global focus.

Skeptical Science does not endorse fracking and the contributors there have consistently expressed concerns that fugitive emissions of methane may erode the emissions advantage that gas has over coal.

Fugitives

The message from recent research is that methane leakage from upstream operations is a potentially large problem, with top-down measurements (i.e., sampling the air in the region of oil and gas facilities in various ways) being consistently much larger than bottom-up estimates (i.e., calculating leakage rates from inventories of equipment and process specifications, and doing on-site sampling). If you want to compare natural gas greenhouse emissions and coal’s it makes a huge difference which figures of gas leakage are correct. No leaks at all would mean that gas produces about half of the GHG emissions of coal. If you believe the higher top-down leakage figures, which may range as high as 9% gas leakage , then gas does not break even with coal until many decades down the road. Bottom-up estimates of methane leaks in the range of 3% or less mean that gas breaks even with coal right away. See Alvarez et al (2011) for more details.

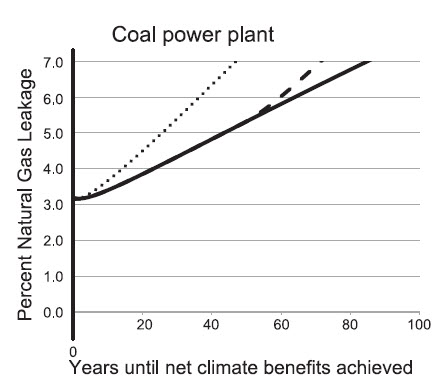

From Alvarez et al (2011), extracted from their Figure 2. The graph shows how long it takes for gas-fired power plants to achieve climate benefits over a coal-fired plants for different rates of methane leakage. At less than 3% leakage, there is an immediate advantage. At 5% leakage rates gas doesn’t break even with coal for 25 years in the case of a pulse (dotted line), or 45 years in the case of permanent fleet conversions of coal power stations to gas (solid line) or for the 50-year service life of a power plant (dashed line). Of course , if gas replaces renewables or nuclear power, the break-even point is never.

It’s worth noting that, at best, gas is about half as bad as the worst climate culprit, coal. That’s something, but half as bad as the worst is not good enough. If we could halve our emissions, that would delay the onset of dangerous climate change. But, to stop global warming, we need to cease emissions altogether. That’s what the physical science and the mathematics tell us: it’s the tough conclusion from hard science.

There’s no 97% or even 94.5% scientific consensus endorsing shale gas as “a safe energy option”

In a September 2014 post, Grealy mentions, with implicit approval, the 97% consensus paper that my Skeptical Science colleagues and I wrote. He said (my emphasis)

“How often have we heard that 97% of climate scientists agree man made warming is real? Similarly, it’s a very high percentage of scientists who see shale as a safe energy option.”

Let’s compare the methodology. The Skeptical Science team read 12,000 abstracts, all of them twice, some of them three times or more. We also asked the authors of the papers to rate the papers for themselves. The results of both methods revealed that about 97% of the scientific papers that express an opinion on global warming endorse the consensus that it is caused by humans. We wrote up the paper and and got it published in a peer-reviewed journal where it has been downloaded 270,000 times in a year and a half.

Grealy simply lists 17 papers selected from references in a paper by Stamford and Azapagic (2014) that, he claims, rebut a study by Howarth et al. One of those selected references is Shindell et al (2009) which argues for higher Global Warming Potential factors to be used for methane. Another is to the Working Group 1 report from the fourth assessment report of the IPCC in 2007. Neither of these publications say anything specific about methane leaks from shale gas operations.

To put it mildly, Grealy’s analysis does not have quite the same level of rigour as ours.

There’s no scientific agreement on this issue yet. A review of 200 studies of methane leaks by American researchers showed that the some of the extreme high leakage figures reported by top-down estimates are probably not representative of the US gas industry. On the other hand, they think, the bottom-up inventory estimates favoured by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) are probably too low. As a Stanford News story reported:

“People who go out and actually measure methane pretty consistently find more emissions than we expect,” said the lead author of the new analysis, Adam Brandt, an assistant professor of energy resources engineering at Stanford University. “Atmospheric tests covering the entire country indicate emissions around 50 percent more than EPA estimates,” said Brandt. “And that’s a moderate estimate.”

A major study led by David Allen of the University of Texas in 2013 found that field measurements at 190 selected onshore natural gas sites showed that some elements of the bottom-up inventories are lower and some higher than EPA estimates and that, overall, if the sample of gas sites is representative, then the EPA leakage figures may be about right, at least for the upstream (the part near the wellhead) of the operations. The representativeness of their sample is questionable: it could have been biased by the sites approved for access by the operators as well as by the self-selection of the companies that volunteered to participate. This is to say that Allen and his colleagues may not have have been given access to sites known to be problematic and that the less diligent companies may not have decided not to participate at all. However, the study does at least show that low fugitive-emissions operations are technically feasible.

But the broader question is far from resolved yet, for example, a recent review paper by the same David Allen remarks:

So, what are the leaks of methane along the natural gas supply chain? Estimates that have appeared in the scientific literature in the past several years have ranged from slightly over 1% (volume of methane emitted as a percentage of the volume of natural gas produced) to more than 10% . This uncertainty range makes it difficult to make policy decisions regarding whether to promote natural gas as a bridge fuel to a low carbon economy. The reasons for the uncertainty are firstly, the large population of sources; secondly, the difference between approaches based on ambient methane concentration measurements (top-down methods) and approaches based on direct measurement of emissions from individual sources (bottom-up methods) and finally, the difference in the extreme values of emission rates, compared to mean emission rates from many of the emission sources in the natural gas supply chain (a ‘fat-tail’ distribution).

It is true that the Howarth et al (2011) estimates of methane leakage (3.6-7.9%) are outliers among the other, lower estimates from bottom-up inventories, but they are still within the range of the top-down measurements. But it is a long way to go from there to a declaration that a big majority of experts see natural gas as a “safe energy option”.

Recent studies such as Limited impact on decadal-scale climate change from increased use of natural gas and The effect of natural gas supply on US renewable energy and CO2 emissions cast doubt on the notion that unconventional gas exploitation is the answer to the climate crisis. Even an author like Michael Levi, no enemy of the fossil-fuel industry, acknowledges that the use of natural gas as a bridge fuel is of limited value if we are to meet 450 ppm CO2 targets. The gas bridge has to be short and it has to lead somewhere apart from perpetual shale gas production.

The climate is not the only thing

As David Smythe and others are showing, the non-GHG risks of unconventional gas development may be significant enough by themselves to stop us from doing it in some cases. The consequences of gas-well drilling on contamination of drinking water are not just theoretical, Robert Jackson and his colleagues have demonstrated in a couple of papers (Increased stray gas abundance in a subset of drinking water wells near Marcellus shale gas extraction and Methane contamination of drinking water accompanying gas-well drilling and hydraulic fracturing) that increased amounts of methane have been found in samples taken near fracking operations in Pennsylvania.

Neither is there a political consensus on the safety of unconventional gas exploitation. The British Labour Party has announced that it will prohibit fracking in all groundwater protection zones, the areas that feed aquifers.

There may well be a majority of scientists who agree that unconventional gas can, with the right regulations and production technology, produce less GHG emissions than coal. There are certainly some experts who believe that, combined with the right emissions policies, natural gas can play an important but limited role in decarbonizing the energy supply over the next few years. None of that makes fracking “a safe energy option”, nor does it make unconventional gas a panacea for the climate crisis. Science provides no green light for unrestricted gas exploitation.

Unconventional gas is a threat to the climate for exactly the same reason that the fossil-fuel companies are excited about it: the resource is huge. But, like it or not, most of the gas simply needs to remain in the ground if we are to meet national and global climate targets. On top of this, exploiting such a massive resource at a level that will provide a significant amount of Britain’s gas needs will require a huge, intense and sustained drilling effort. By itself, this would likely pose unacceptable risks and quality-of-life problems, especially in the densely populated areas of England. I will explore this some more in the next post.

The final instalment in this series is titled: Fracking 3: Quantity has a quality all of its own

The previous article was: Fracking 1: Spot the Charlatan

Pingback: Sanders, Clinton, Rubio, and Kasich answer climate debate questions | Dana Nuccitelli – Enjeux énergies et environnement